by Gavin Daker-White, Research Fellow, Multimorbidity theme, NIHR Greater Manchester PSTRC, The University of Manchester

“What we’ve got here is failure to communicate” (Cool Hand Luke, 1967, Warner Bros/Seven Arts)

This is the last of 3 blogs that discusses the results of a review of qualitative studies of patient safety in primary care as undertaken by researchers at the NIHR Greater Manchester PSTRC and NUI Galway. The review, published in August 2015 (and available here) examined 48 studies grouped into 5 topic areas:

- Patients’ perspectives around safety (8 articles)

- Staff perspectives on safety (14 articles)

- Medication safety (10 articles)

- Organisational or management issues (7 articles)

- Care transitions between primary care and hospitals (9 articles)

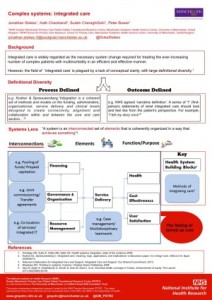

The story of patient safety contained in the articles reads essentially as a clash between imperfect and infallible human beings on the one hand, and standardised medical systems on the other. In the final part of the series of blogs that discuss the results of this review we examine the findings concerning the organisation and delivery of care.

Of the 48 papers included in the review, 7 were focused on systems issues and it was noteworthy that most were ethnographic in nature; that is they relied on observation and interviews by researchers examining health services settings during normal working hours. Most of these studies had staff as participants, as opposed to patients. Whereas the studies concerned with staff perceptions of patient safety also included much concerning the organisation of care, such findings were not evident in the studies where patients were interviewed. For patients, the only relevant finding was that patients appeared unaware of normal clinical protocols or procedures, against which they would have been able to gauge and judge their own experiences, e.g. of waiting to be informed of test results.

One group of findings concerned the characteristics of computer systems that could variously increase or reduce the potential for errors according to features of design or quality of stored information. In other instances it was simply that staff had not been trained properly to use new equipment or software. Procedural standardisation of all kinds could seemingly work for or against safety in different circumstances. Thus both EHRs and clinical protocols had the capacity to create an illusion or even a false sense of security. New protocols had the capacity to create additional workloads on already overworked staff and could have knock on effects that weren’t considered prior to implementation. These findings point to a need to better investigate whether a ‘one size fits all’ approach is preferable (in safety terms) as opposed to one based around the uniqueness of individual and ‘complex’ patients.

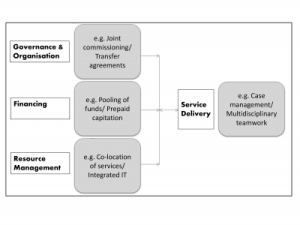

A systems approach was preeminent in the nine articles that reported findings from studies about ‘handoff’ or ‘handover’ processes between hospitals and primary care. The main problems included patients being discharged from hospital with insufficient information or medical supplies (e.g. drugs or bandages) and the vulnerable characteristics of some patients. In the same way that patients were ignorant about how processes work in primary care, GPs were perceived to view hospitals as a “kind of black box” (Russ et al., 2009) and might be uncertain about how or whether communication between care providers takes place (Arora et al., 2010).

Across the 48 studies, the following aspects of health systems were seen to compromise or threaten patient safety in primary care:

- Dispersed or insufficient patient information

- Byzantine organizational structures

- Drugs and care not transferable between primary care and hospitals

- Non compatible systems between sectors

- Budgetary constraints

- Perceived inflexibility and irrelevance of guidelines (e.g. in multimorbidity)

The findings of the studies pointed to the following ways of improving health systems in terms of patient safety:

- · Improved medical records

- Effective communication between primary and secondary care

- Better resources

- Reliable systems

- Timely accessibility and updatability of information

- Standardization and improvements in knowledge, regulations, reporting and processes

References

Arora VM, Prochaska ML, Farnan JM, D’Arcy MJt, Schwanz KJ, et al. (2010) Problems after discharge and understanding of communication with their primary care physicians among hospitalized seniors: a mixed methods study. J Hosp Med 5: 385-391.

Russ AL, Zillich AJ, McManus MS, Doebbeling BN, Saleem JJ (2009) A human factors investigation of medication alerts: barriers to prescriber decision-making and clinical workflow. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2009: 548-552.